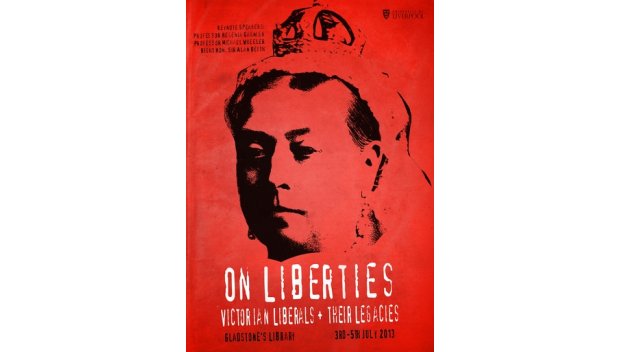

On Liberties: Victorian Liberals and their legacies

Gladstone’s Library, 3rd-5th July 2013

The first weekend of July saw an eclectic mix of doctoral students, early career scholars, and permanent postholders, from a range of institutions across the UK and the USA, converge on Gladstone’s Library in Hawarden, North Wales to discuss ‘Victorian Liberals and their Legacies’. The conference sought to bridge literature and history, and the nineteenth and twentieth centuries, so as to arrive at a better understanding of what ‘Liberalism’ might have been, how it might have originated, how it might have been transmitted, and what consequences it might have had. This was, clearly, an ambitious agenda for three days. Luckily the sun shone throughout, and if we cannot now claim to have all the answers to these questions, all the attendees at least came away with important new questions to ask.

The conference began with a panel on the grand theme of ‘Liberalism: Definitions and Mechanisms’. In the event this was composed of three political historians, who usefully opened up some key themes in nineteenth-century Liberalism. David Craig’s paper on the emergence of the languages of ‘liberalism’ and ‘liberality’ around the turn of the nineteenth century, in particular, set the conference on its feet with a vigorous and compelling dissection of what people actually meant by the term ‘liberal’ before it began to be understood in a primarily political sense. Emily Jones, discussing Liberal attitudes towards Edmund Burke around the time of the Home Rule crisis of the 1880s, took the discussion of these important issues of chronology a stage further, suggesting that the search after political ‘isms’ and abstract political ideology was an innovation of the later nineteenth century. The first question period, moreover, established the tone of inquisitiveness, openness, and engagement which was to characterise post-panel discussions throughout the conference. The first dinner, and the subsequent trip to the impressively well-appointed village pub, only cemented this atmosphere of intellectual openness and general conviviality.

The number of papers delivered over the next two days, combined with the fact that many of them were arranged in parallel sessions, makes it impossible here to do anything but pick out certain themes and highlights. The panel on ‘Liberals, Slaves, and Aliens’ offered a fascinating set of papers on how liberalism dealt (or failed to deal) with problems of race, exclusion, and unfree labour, approaching these issues through the very different lenses of the high political debate over the forcible suppression of the slave trade in early-Victorian Britain, literary responses to the Aliens Act of 1905, and South African imperial romance novels. Liberals, it emerged, found it extremely difficult to agree on where the boundaries of the political community ought to be drawn. The methodological tensions evident in this panel between the historian and the students of literature were even more pronounced in the panel on ‘Commons Ground’, where two highly theoretical close readings of Anthony Trollope’s political novels ran up against a much more straightforwardly historical analysis of the same, alongside a thorough biographical treatment of James Stansfeld MP, one of the leading lights in the late-Victorian campaigns against the Contagious Diseases Acts. The discussion that emerged, of the relationship between liberal politics and ‘liberalism’ as an approach to literary style, was a particularly stimulating one. The final panels focused more narrowly on literature: that on ‘Literary Liberalism’ threw together the Brownings, Thomas Arnold, and Ralph Waldo Emerson; that on ‘Legacies’ considered how far E.M. Forster was responding and/or contributing to debates over the ‘new Liberal’ (i.e. proto-collectivist) politics of the Edwardian era, while the final paper of the conference looked at the representation of the Victorian eccentric Henry Ashbee in two novels published in the last eleven years. In these panels we were confronted with a huge variety of approaches to ‘liberalism’ and ‘liberty’, from the ‘liberties’ taken with the representation of Ashbee, to Arnold’s contextually specific arguments about the extent to which religious liberalism could be allowed to run, to the (implied) relationship between the Brownings’ liberal social contract and Robert Browning’s political poetry. Nobody could have come away from these diverse panels and papers without being forced to confront and reconsider their assumptions about what makes a ‘liberal’, or about the unity and historicity of the attached ‘ism’. In this respect the juxtaposition of historians and literary scholars, while often challenging for at least some representatives of the former group, was one of the most intellectually productive aspects of the conference.

Each of the keynote lectures added important ingredients to this pleasantly simmering broth. Michael Wheeler’s opening address on ‘Religion and Science in the 1830s and 1860s’ offered an orientating conspectus of some of the major intellectual contexts from which nineteenth-century Liberalism took its shape; one-time deputy leader of the Liberal Democrats Alan Beith provided an insider’s view of the ‘legacies’ of political Liberalism, discussing the costs and benefits of possessing a ‘creed’ for political parties in general (and for the Liberal Democrats in particular), while providing a range of incidental insights into the contemporary politics of coalition; and Regenia Gagnier, in what must be seen as a high point of the conference, spoke compellingly on ‘The Global Circulation of the Literatures of Liberalization’, fusing philosophy, psychology, history, and literature, in a compelling demonstration of interdisciplinarity done right.

For all the intellectual stimulation on offer from the conference proper, however, this attendee drew most of all from the opportunities it presented to leaf through Gladstone’s personal library. It was extraordinary, after so many years of reading about the man, to be confronted with the massed physical evidence of his voracity; and, in particular, to pull down a volume of Mill from the shelves, only to find it inscribed to the statesman ‘from the author’. Here was confirmation, perhaps, of the wisdom – and the necessity – of the conference’s efforts to bridge the gap between literature and politics. Many thanks are due to Matthew Bradley and Louisa Yates for organising such a splendid conference in such exceptional surroundings, and to the Library staff for their unfailing friendliness and efficiency.