At Gladstone’s Library we rotate our History Room display every month to focus on an aspect of Gladstone the man, or our extensive library catalogue. This February I decided to give some of our lesser-known collections a little TLC by presenting a display on ‘Tales of the Supernatural: The Library’s Hidden Creature Features!’ Additionally, to give you all some extra background on this exciting topic, I’m writing this blog for our website.

For an organisation that is famous for its extensive collection of Prime Minister William Ewart Gladstone’s books, Gladstone’s Library has a surprising number of works on horror and the supernatural. We have literary, historical and theological works on various ‘monsters’ including Dracula, Frankenstein’s monster, the Werewolf, the Mummy, and many more. We also have several reference books on this subject (which can be found in the Annex corridor with the red ‘REF’ stickers) such as Chambers’ Dictionary of the Unexplained (K 40/71 REF); and a significant DVD collection on our main staircase landing which includes classic and modern horror works. It is the oft neglected connections between the monster stories we see repeated on film and television today, with the literary, theological, and history books present in our library, that I wish to explore.

Most people will be familiar with names such as Frankenstein’s Monster, Dracula, Imhotep the cursed Mummy, and other classic monsters from films and TV. Some may even have read Mary Shelley’s Frankenstein or Bram Stoker’s Dracula and have an appreciation for the source material of these film adaptions. However, it is rare that someone who watches films such as Dracula Untold or The Bride of Frankenstein will then delve deeper into the origins of the history, theology, literature and mythology that inspired the creation of creatures such as vampires and werewolves. However, there is a growing body of scholarly work examining these connections and the importance of ‘new’ media in interpreting and disseminating these myths and stories in society today.

|

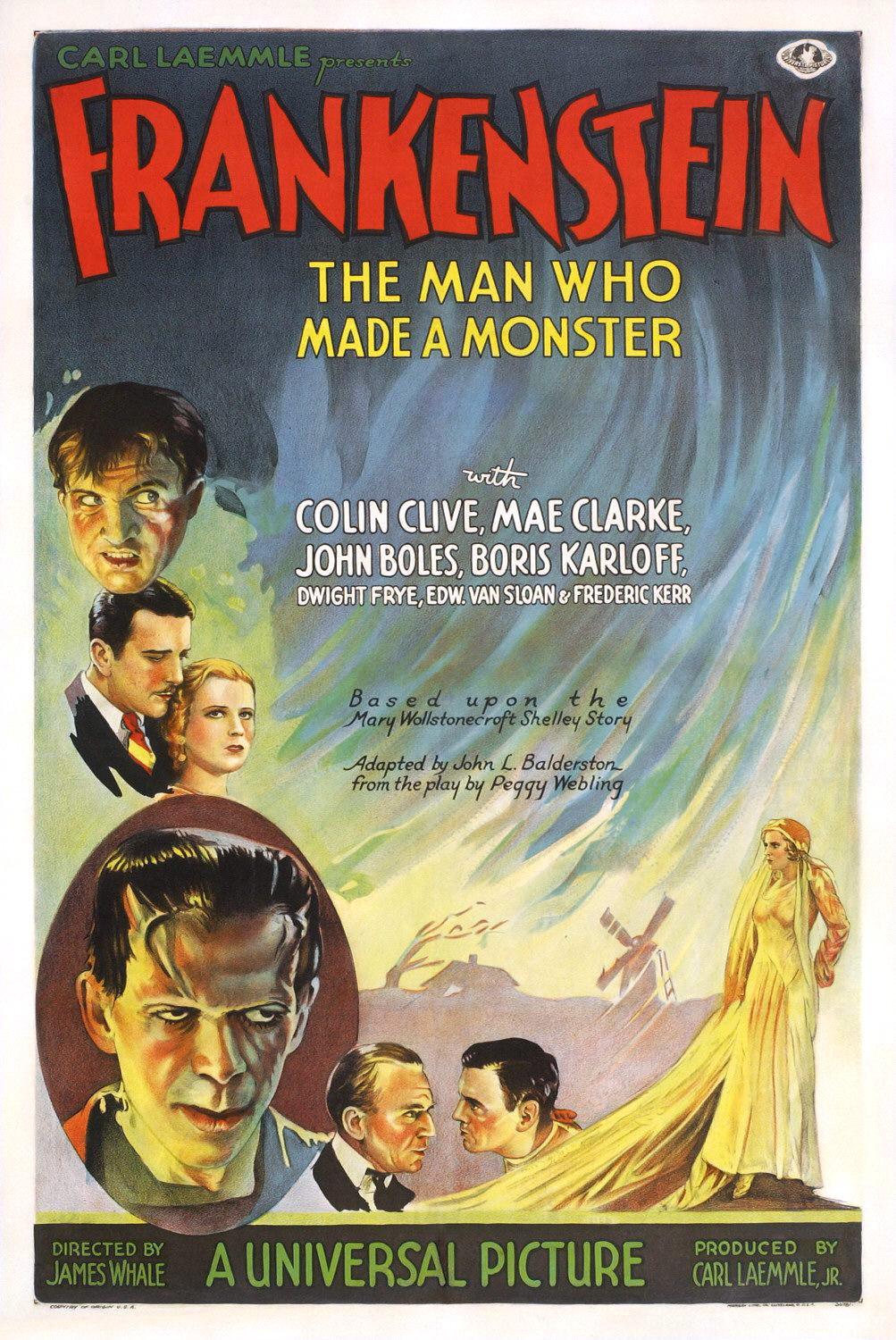

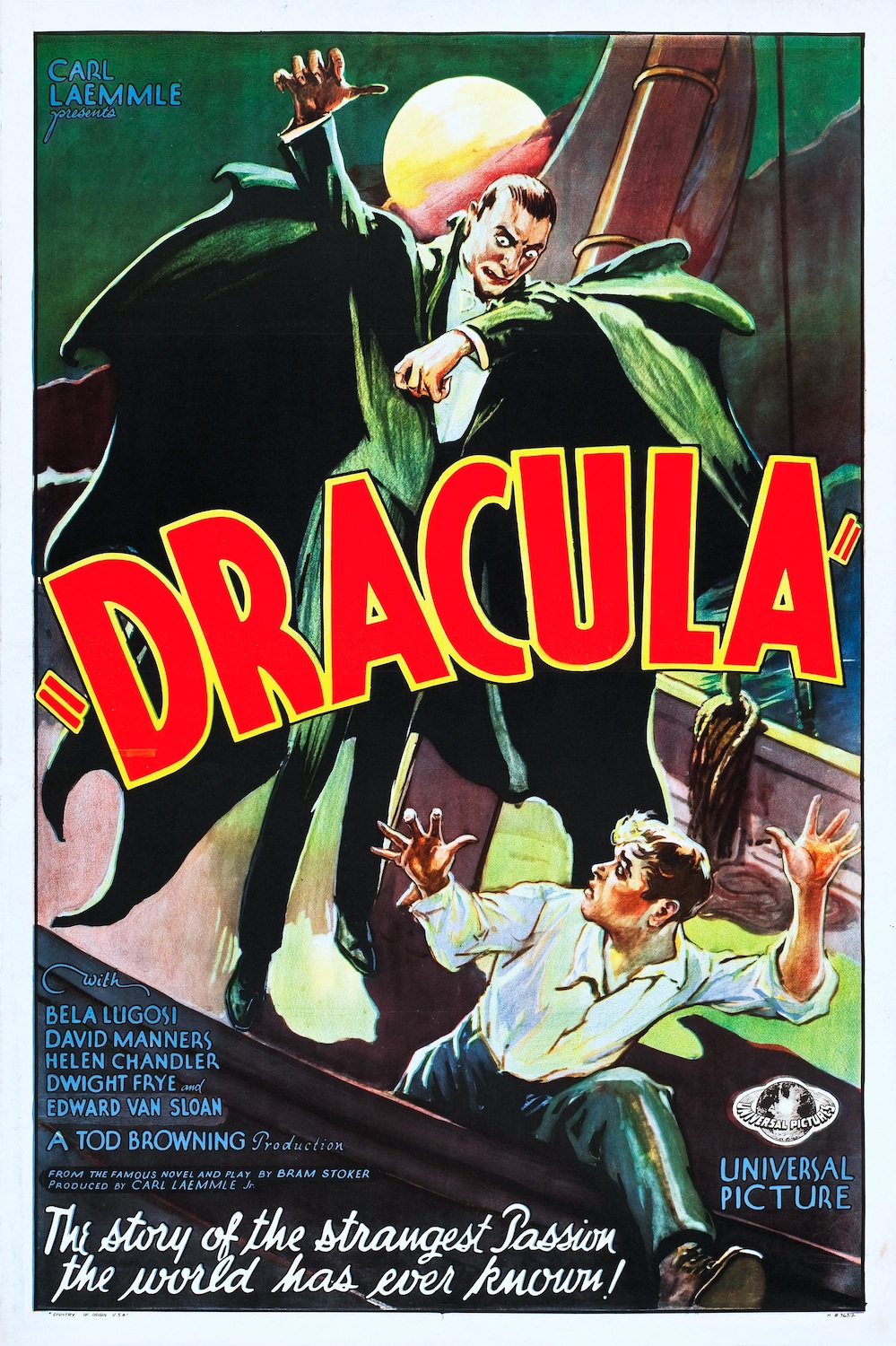

The earliest adaptions of these Horror ‘monsters’ in film came in the 1920s when movie studios, and particularly Hollywood’s Universal Pictures, began using Shelley and Stoker’s source material to create blockbuster films. In 1922, German director F. W. Murnau released the silent film Nosferatu: A Symphony of Horror; an expressionist piece that has been widely acclaimed by fans since its release but which was regarded with horror by Bram Stoker’s estate and which resulted in a court case that left all but one lucky copy of the film burned on orders of a judge. The transition of these horror stories from page to screen has clearly not always been a simple one with copyright and licensing laws continuing to be a major issue for anyone dealing with intellectual property. However, Universal Pictures had an easier time creating their 1930s adaptions as Stoker never registered a copyright for his work in the United States and Shelley’s copyright of Frankenstein had long since been sold and then expired – leaving the work in the public domain and open to more creative interpretation as time went on.

Enduring stars emerged from Universal’s movie adaptions. Bela Lugosi became THE Dracula to audiences and continued to regularly play the character on stage and screen until his death in 1956. Boris Karloff also found fame due to his portrayal of the Monster in Frankenstein, as well as originating the character of Imhotep the Mummy in Universal’s 1932 The Mummy, which may be familiar to modern audiences through its 1999 reboot, its subsequent sequels and then a second reboot in 2017. The early film adaptions of these horror works were often critically and commercially lauded and not confined to the rules of today’s horror genre which is not often taken seriously as an ‘art’ by critics. Through these films, these characters have endured and presented enticing properties for film studies to reboot, in order to capitalise on their popularity.

|

However, there are longer histories for almost all of these monsters that pre-date the silver screen. The creation of the vampire myth is lost to time, however, one of the earliest examples is that of the Indian Baital. A spirit who hangs from trees and can present itself in many different animal and human disguises (including memorably, as a giant bat) – the Baital is analogous to Western vampires and was likely a major influence on Gypsy myths of ‘vampires’ that were buried and then raised from their grave to drink their blood. The Baital features in one of Gladstone’s own books, Vikram and the Vampire: Or, Tales of Hindu Devilry, which is a translation and adaption of the Baital Pachisi by Sir Richard Burton. The Baital Pachisi is an ancient Sanksrit work compiled in the 11th Century which features one of the earliest surviving mention of ‘vampires’ in fiction. It also presents the Vampire as more of a trickster than a demonic figure, who even saves the King’s life in the end of the novel – something that demonstrates how the vampire as a ‘monster’ has always been a fluid interpretation. This work belonged to and was likely read by Gladstone and shows how even English adaptions of the vampire myths of other cultures pre-date the publication of Bram Stoker’s Dracula in 1897.

Some of the other frequent horror movie monsters have no direct literary inspiration. The Werewolf first appeared in film in Universal’s 1935 Werewolf of London, and then more famously in its 1941 film, The Wolf Man starring Lon Chaney Jr in iconic make-up which would go on to have a significant influence on Hollywood depictions of werewolves today. Neither of these films were based on literary works, but instead on the legend of the werewolf that has existed since at least the Ancient Greeks with werewolf hunting and executions becoming commonplace in Germany and France during the witch trials in the 16th and 17th centuries. Therefore, this character has a historical basis, or at least that of a legend commonplace throughout history. Books in the library like David Williams’ Deformed Discourse: The Function of the Monster in Mediaeval Thought and Literature (1996) can give more information about how lycanthropy became such a popular accusation in the Middle Ages and how it has endured in the popular consciousness till the present day.

The Mummy is another example of a historical figure being co-opted by film and TV media into a horror villain. The discovery and opening of Tutankhamen’s tomb in 1922, and the subsequent death of the expeditions financial backer Lord Carnarvon by a ‘mummy’s curse (or blood poisoning to normal folks), led to a media frenzy that film studios were eager to capitalise on. Before this the re-animated Mummy as a monster with a curse does not seem prevalent in popular culture or media. For hundreds of years people in the Middle East and North Africa had been using ground up mummy parts as medicine, with the belief that it would cause healing rather than afflict a patient with a curse. In fact, while Mummy movies did exist before the 1920s they largely involved the resurrection of a Mummy to a complete human body (usually that of an attractive lady) such as Cleopatra in Georges Méliès 1899 silent film, Robbing Cleopatra’s Tomb, or the Thanhouser Company’s 1911 film The Mummy, wherein a beautiful, female mummy is resurrected, rejected by the man who recently bought her at auction, and then swiftly married off to his Egyptologist father-in-law-to-be.

|

In this way we can see that there is no uniting Mummy curse myth the like of which characters such as Frankenstein and Dracula can claim, with Universal Pictures’ 1932 film The Mummy instead originating a new mythology around a resurrected High Priest Imhotep looking for his lost love Ankh-es-en-amon in the present day, a plot and character roster that has been re-used and adapted in the film’s 1940s sequels, the Hammer Horror Mummy films of the 1950s, ‘60s, and ‘70s, the 1999 reboot of The Mummy and its sequels, as well as the 2017 Universal Dark Universe The Mummy reboot. Again, we can see how people have been the driving factor in adapting historical figures into popular media monsters without any real basis. To learn about the ancient origins of the real mummies and the lack of curses inherent in their history then please enjoy a number of works on this time period that we have in the library such as E.A. Wallis Budge’s 1893 The Mummy: Chapters on Egyptian Funeral Archaeology.

There are undeniable links between books and popular media, as well as between the mythology, theology, history and literature that inspired the original works we now may see as far removed from the popcorn movies and literature that characterise these ‘horror’ monsters today (Teen Wolf and Twilight). However, Bram Stoker’s Dracula, and Mary Shelley’s Frankenstein, were the popular fiction of their day and the former itself is an adaption of the historical figure of Vlad the Impaler; while the latter’s subtitle, The Modern Prometheus, shows links to Ancient Greek culture. Therefore, the evolution of these horror monsters can be seen as a completely normal example of how human beings adapt stories and characters for society’s, and their own, needs with the links between some of the ‘serious’ works we hold in our library collections and the ‘popular’ media that is consumed every day, being closer than you think.

Our ‘Tales of the Supernatural: The Library’s Hidden Creature Features!’ display is currently on display in the History Reading Room at Gladstone’s Library from 1st – 28th February 2019. See it on a Glimpse of Gladstone’s Library.

Bibliography:

(R 34 She/38) Higgins, David. Frankenstein: Character Studies. Continuum Character Studies. London: Continuum, 2008.

(U 40/68) Bann, Stephen, ed. Frankenstein, Creation and Monstrosity. Critical Views Series. London: Reaktion Books, 1994.

(R 34 She/24) Florescu, Radu. In Search of Frankenstein: Exploring the Myths Behind Mary Shelley’s Monster. London: Robson Books, 1999.

(R 37 Sto/6) Trow, M. J. Vlad the Impaler: In Search of the Real Dracula. Stroud: Sutton Publishing, 2004.

(WEG/K 21/BUR) Burton, Richard F. Vikram and the Vampire: Or, Tales of Hindu Devilry. London: Tylston & Edwards, 1893.

(A 15/34) Budge, E.A. Wallis. The Mummy: Chapters on Egyptian Funeral Archaeology. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 1893.

(K 31/61 REF) Lurker, Manfred. Dictionary of Gods and Godesses, Devils and Demons. London: Routledge, 1987

(K 29 / 17) Trigg, E.B. Gypsy Demons and Divinities. Sheldon Press, 1975.

(E 19.8/264) Jobling, J’annine. Fantastic Spiritualities: Monsters, Heroes and the Contemporary Religious Imagination. London: T & T Clark, 2010.

(B 00/92 REF) Toorn, Karel van der, ed, Bob Becking, ed, and Pieter W Horst, ed. Dictionary of Deities and Demons in the Bible. 2nd revised edition Eerdmans, 1999

(R 39/13) Pulham, Patricia, ed, and Rosario Arias, ed. Haunting and Spectrality in Neo-Victorian Fiction: Possessing the Past. Basingstoke: Palgrave Macmillan, 2010.

(33.3 /124) Dickerson, Vanessa D. Victorian Ghosts in the Noontide: Women Writers and the Supernatural. Columbia: University of Missouri Press, 1996.

(K 40/74) Thurston, Herbert. Ghosts and Poltergeists / by Herbert Thurston; Edited by S. H. Crehan. London: Burns & Oates, 1953.

(46/C/1 ) Canaan, T. Haunted Springs and Water Demons in Palestine. Studies in Palestinian Customs and Folklore [2], Journal of the Palestine Oriental Society, vol. 1, p153-170 (1922)

(E 19.8/304) Garrett, Greg. Living with the Living Dead: The Wisdom of the Zombie Apocalypse. New York: Oxford University Press, 2017.

By Sophie Hammond, Graduate Work Experience