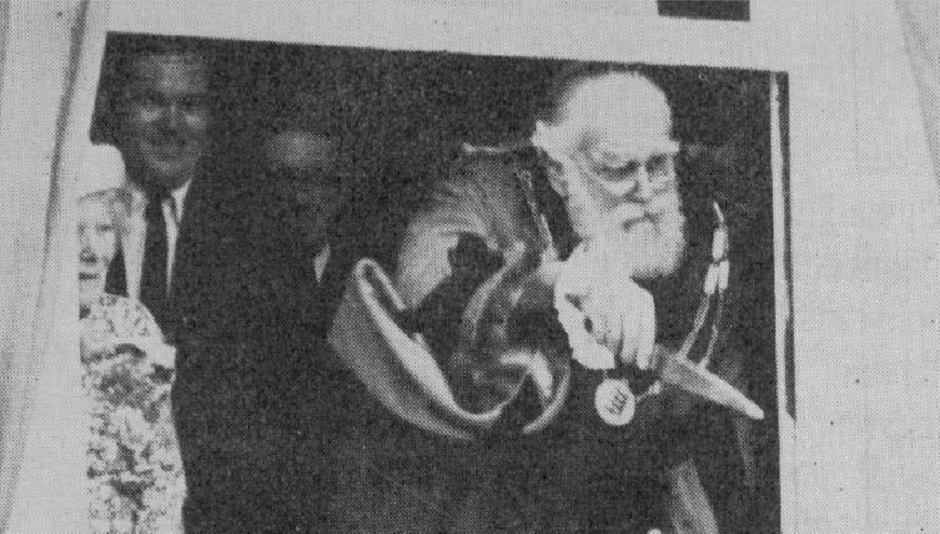

Image: Alec Vidler, Gladstone’s Library Warden (1938 – 1946)

Before World War II, when the library was only 30 years old, Alec Vidler, the then Warden of St Deiniol’s Library, was preparing for a ‘decrease in the number of ordinary visitors’, which he called ‘inevitable’ is his 1938 report to the board of trustees.

He believed that the war, which was set to consume the world, would leave no time for scholarly learning or reflection. There was even talk of the RAF taking control of the building and using it as a base for officers – however when the expense of rehousing and maintaining the collection became clear, it was decided that other premises could be found.

The library itself was relatively untouched by the war. The Annex and Reading Rooms were blacked out to continue late night working. In his autobiography the Warden records that it was his priority that the library should continue to function as normal; so much so that he pitched a tent in the garden where he could sleep in order to free up room in the hostel in case it was needed for evacuees!

Of course, the war’s reach was felt. The obvious restrictions of rationing, shortages of staff and the destruction of Hawarden train station all hit close to home. Yet, despite all expectations, war-time was the busiest period that the library had experienced since its beginning.

In 1940, just two years after Vidler is preparing for the worst, he writes:

‘I am much encouraged by the increasing number of people who are looking at St Deiniol’s as in some sense a centre, where they can come and stay from time to time (even if just for a few days) for reading, thought and consultations; and who say that it is more important than ever during war-time that the opportunities we provide should remain available; and that St Deiniol’s can make a valuable contribution in preventing what is called ‘the black out of the mind’, which is recognised as a serious danger in these times.’

He talks of the popularity of the library with soldiers home on leave and of it being used as a ‘respite’ for clergy from badly raided areas. Perhaps it was here, in the middle of all the civil unrest, where physical representations of the violence and discord were felt throughout the continent, that the library revealed its purpose.

Today we once again find ourselves in the midst of an unexpected surge in popularity, with a record number of users coming through our doors. One can’t help but draw parallels: a time of political unrest, the rise of populist politics and obvious divisions. And though we are not surrounded by the ruins of buildings or haunted by an ever-growing list of the dead (at least in the UK), we are constantly bombarded with information from every direction. Television, radio, online newspapers and any social media platform you care to mention amplify our anxieties.

Conceived by a man dedicated to the progression and liberty of all, Gladstone’s library stands, as it did in 1940, against the black out of the mind. When people need them most, Gladstone’s belief in tolerance, education and democracy can always be found in the books he left behind and the culture he created here. As current Warden, Peter Francis told the New York Times last year:

‘In our current climate, they [liberal values] need reaffirming, exploring and celebrating more than ever.’

By Elspeth Brodie-Browne, Intern

The Islamic Faith & Culture project, based in the House of Wisdom at Gladstone’s Library, was set up in 2010 to address one of the key social conundrums of contemporary society – the relationship between Muslims and non-muslims. The collection promotes understanding of the contributions of Islam as a faith and Muslims as rich and vital communities in the modern world by providing a space for mutual learning and engagement. Read more about the Islamic Reading Room and its collection here.