Drawing Blood, Drawing Poison, Drawing Fire – a pre-launch Q&A with the artist, Simon Grennan.

Funded by the Arts Council and led by artist Simon Grennan, ‘Drawing Blood’ is a new collaborative art project that creates a new online exhibition of twenty new, original animated artworks. Hosted by Gladstone’s Library, the online exhibition will also be available at Contemporary Art Space Chester and at Aura libraries in North Wales, including Broughton, Buckley, Mold, Deeside, Holywell, Connah’s Quay and Flint.

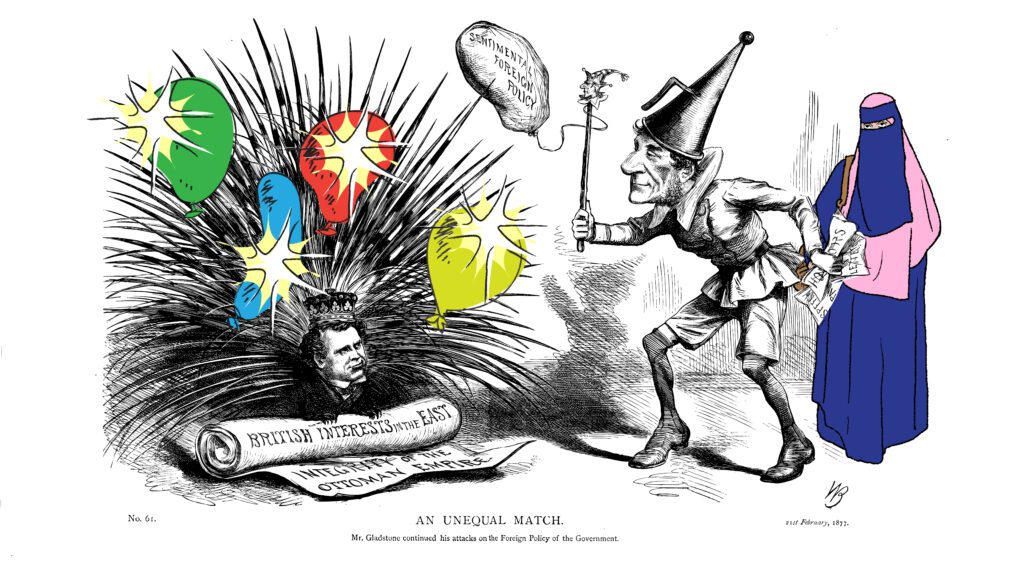

The new artworks are inspired by a book Simon found in the Gladstone’s Library collections. Dating from 1878, Gladstone from Judy’s Point of View collects cartoons satirising one of the hot topics of the period – liberal political opinion. As one of the major Liberal politicians, William Ewart Gladstone is often in the firing line of Judy’s cartoonists. In the tradition of political artists everywhere their pens puncture any political pomposity, drawing Gladstone (and others) not as respected statesman but as wobbly juggler, unstable acrobat, indecisive whirligig, pram-pushing lady, and many more.

Ahead of the exhibition’s launch, Simon gave us some exclusive insights into the production process. They’ll be posted on this blog each week: for a full list, please visit the project’s home page: https://www.gladstoneslibrary.org/reading-rooms/digital-gladstone/drawing-blood-drawing-poison-drawing-fire

Did the Victorians find these sorts of political cartoons funny?

Victorian readers did find the cartoons funny, very possibly in the way that readers of newspapers and current affairs journals today find the satirical cartoons and their style of commentary funny. The laughter was sophisticated, however. Although there is a pantomime feeling about these cartoons, readers had to know the politics and the political actors to understand them. For readers, there was a sense that you had to be fairly interested in current affairs to understand why a politician might be drawn as a porcupine and another as a baby in a pram, or why these people were bashing their heads against an Egyptian pyramid – and to laugh at these depictions. Readers could pat themselves on the back if they understood and felt the humour. The drawings made them feel like they were in the swim, laughing at an in-joke.

Oedd y Fictoriaid yn gweld y mathau hyn o gart?ns gwleidyddol yn ddoniol?

Roedd darllenwyr Fictoraidd yn gweld y cart?ns yn ddoniol, yn bosibl iawn yn y ffordd mae darllenwyr papurau newydd a chylchgronau materion cyfoes yn ystyried y cart?ns dychanol a’u harddull o sylwebaeth ddoniol. Roedd y chwerthin yn soffistigedig, fodd bynnag. Er bod yna deimlad o bantomeim am y cart?ns hyn, roedd yn rhaid i ddarllenwyr wybod y wleidyddiaeth a phwy oedd yr actorion gwleidyddol er mwyn eu deall. Ar gyfer darllenwyr, roedd yna deimlad bod yn rhaid i chi gael dipyn o ddiddordeb mewn materion cyfoes i ddeall pam y byddai gwleidydd yn cael tynnu ei lun fel ballasg ac un arall fel baban mewn pram, neu pam bod y bobl hyn yn taro eu pennau yn erbyn pyramid Eifftaidd – ac i chwerthin ar y darluniau hyn. Gallai darllenwyr daro eu hunain ar eu cefnau os oeddent yn deall ac yn teimlo’r hiwmor. Roedd y lluniau yn gwneud iddynt deimlo eu bod yn nofio, yn chwerthin ar jôc.