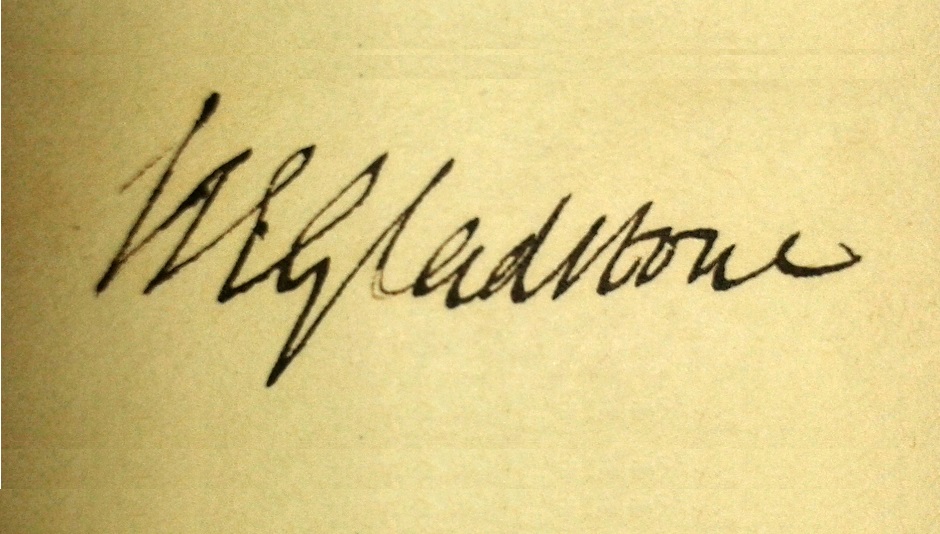

William Ewart Gladstone, the founder of Gladstone’s Library, was a diligent and intelligent man. Apart from being Britain’s longest serving Prime Minister to this day, he also managed to read 22,000 books and even found the time to annotate 11,000 of them. And not just in his native language, English; he also annotated his books in at least five other languages: Latin, Italian, Greek, French and German. Since German is my mother tongue, I was entrusted with the task of translating Gladstone’s German annotations into English. A very interesting and fascinating task, I must say, and one which I am just coming to the end of. But it also had its challenges. In this blog, I want to share the experiences, troubles and enlightenments I experienced during the task of translating Gladstone’s annotations.

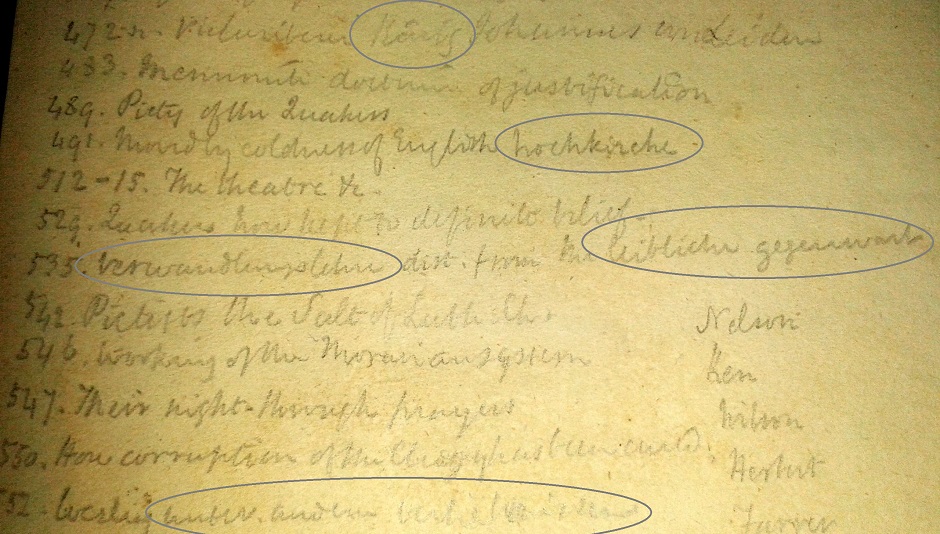

There are various kinds of annotations in Gladstone’s books: he wrote marginal annotations, single words or even full sentences next to the text itself; he wrote indexes with page references at the end of his books; sometimes he just underlined words or sentences or drew notice lines next to a paragraph.

Working on Gladstone’s German annotations has been a great way to gain a deeper insight into the man’s life and way of thinking, but there was also one big difficulty: his handwriting. It can often be difficult to read another person’s handwriting, but Gladstone frequently wrote in pencil which has led to the words fading over the years. On top of that, his handwriting became shakier and more illegible as he grew older. Not knowing for certain whether the word I was trying to decipher was German or English or even another language altogether didn’t help! From time to time, when I came across an especially difficult word to decode, I looked to the statue of Gladstone in the Reading Rooms for clues, but of course that didn’t solve anything. Nevertheless, I liked the challenge and it was very satisfying when I finally got the words right…

(WEG index found in: Moehler, John Adam. Symbolik : Oder, Darstellung der Dogmatischen Gegensätze der Katholiken und Protestanten Nachihren Öffentlichen Bekenntnissschriften. Mainz: Kupserberg, 1843. For a better understanding of which parts of the index are written in German, I have encircled the German words in grey).

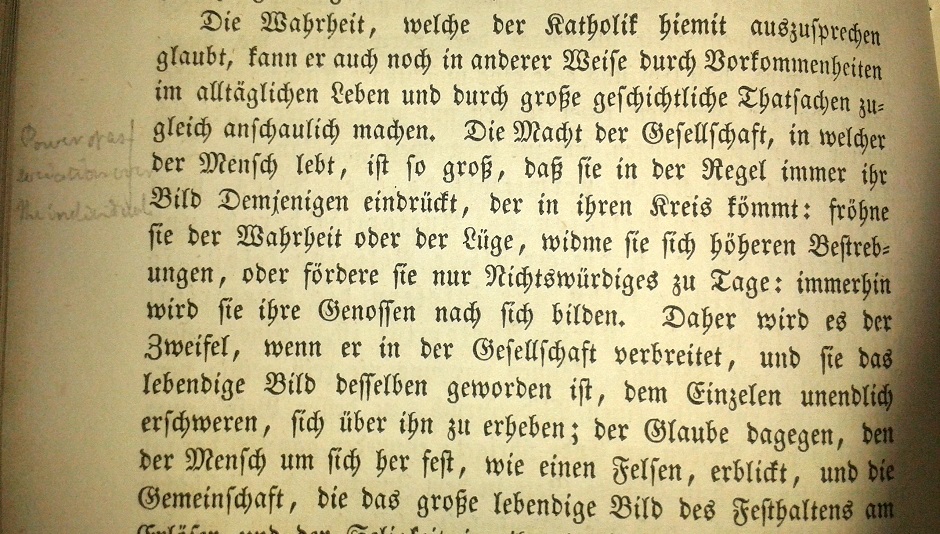

When I couldn’t seem to get what a particular word meant, I tried to hypothesise what it could be by reading through the context of the book itself. Here I was again confronted with difficulties: old German type-writing. This is very different from the printed fonts used today and at first very confusing to read, as the letters look very strange.

After a while however, I managed to get the hang of it and in the meantime, my admiration for Gladstone grew, as he was apparently able to read this font perfectly, whereas even I, a native speaker, struggled!

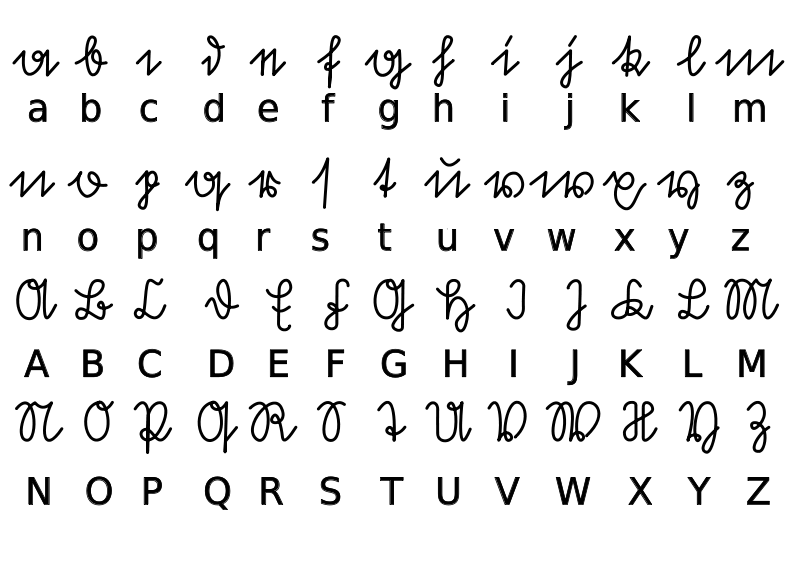

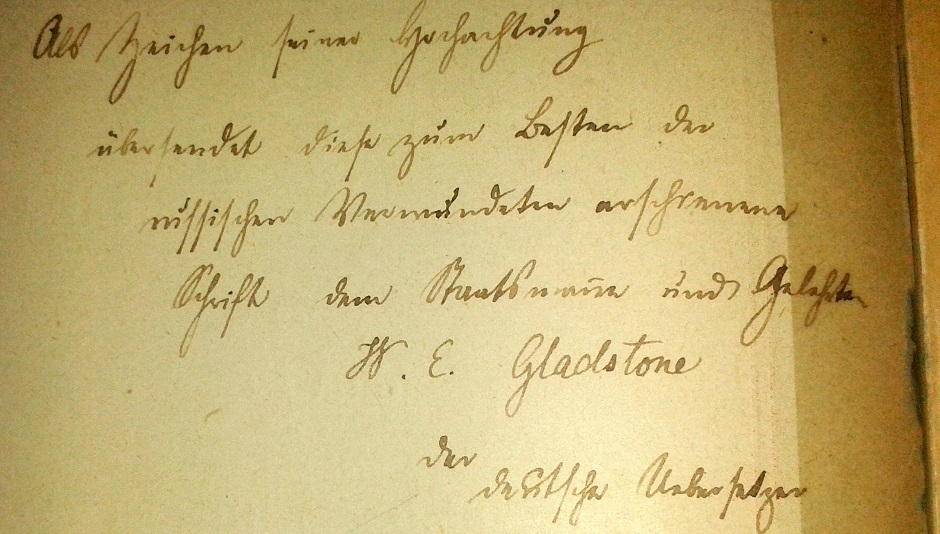

After a while, I discovered that not all of the annotations in Gladstone’s books came from his own hand. In many of the books previously owned by Gladstone one can also find handwritten dedications to him and naturally I could not disregard these. It soon turned out that I should not have moaned about Gladstone’s handwriting so much, because what awaited me at this point was much worse: old German handwriting called Suetterlin. Let me quickly give you some background information on this particular German type of writing, so that you can understand the full extent of my struggles.

Suetterlin, also commonly called ‘the German handwriting’ was taught in German schools from 1915 until 1941, when it was replaced by a newer system. My grandmother could possibly still read it without too many problems, but she would probably be the only person I know who could.

Here is a picture to show you what Suetterlin letters look like:

This is, of course, the perfect example how Suetterlin should look. In reality though, since it occurs only in handwriting, the letters become more scrawled. It becomes very difficult to distinguish between ‘e’ and ‘n’ or even ‘u’ and ‘m’. The same goes for ‘s’ and ‘t’ and the letters ‘a’, ‘o’ and ‘q’ melt into one scribble as well.

(Dedication to WEG found in: Hemans, Felicia. Der Letzte Constantin Von Felicia Hemans und Wordsworth’s Politische Sonnette / Aus Dem Englischen Ubersetzt Von Christian Hönes. Stuttgart: 1878.)

So in many ways decoding the dedications was a lot of detective work. Feeling like Sherlock Holmes, I sat there, a magnifying glass in my hands, trying to compare the letters with the Suetterlin table open on my screen. It worked, but progress was slow. Why did Germany have such a complicated writing system back in those days??

All in all, I can say that once I’d overcome the frustration and actually got a paragraph or even a single line that I could then translate, I realised that it was worth the annoyance. It was so interesting to get to know more about Gladstone and I can’t help but admire him and his intelligence and his fluency in various languages. I thought when translating his annotations, that I would get to know Gladstone a bit better and make a connection with him. In many ways I definitely have, but what I didn’t expect was that I would learn so much about my own cultural history. I was never concerned with old German handwriting, but now I have the feeling that I have a very good grasp of it and that makes me very proud. Thanks, Gladstone!

A few examples of my translations are as follows:

German dedication: Als Zeichen seiner Hochachtung Übersendet dies zum Besten der Russischen Verwundeten anschr [illegible] Schrift dem Staatsmann und Gelehrten W. E. Gladstone der deutsche Uebersetzer Christian Hönes.

English translation: As a sign of his esteem sends this to the best of the Russian wounded [illegible] the writing (to) the statesman and scholar W. E. Gladstone the German Translator Christian Hönes.

Index: 535. verwandlungslehre [= German for ‘doctrine of transfiguration’] dist. from the leibliche Gegenwart [= German for ‘bodily presence’]

Marginal note: ‘ente’ [German: duck] beside Trin’s lines ‘Swam a-shore, man, like a duck; I can swim like a duck, I’ll be sworn’, Act II Sc II of The Tempest

If you’d like to read Gladstone’s annotations in any language yourself, you can find them online on the GladCat.

If you are specifically interested in German annotations, please ask at the Enquiry Desk.

Marina Prenzel